Brief explanation

Teletext is a weird technology. Although often ridiculed as completely archaic, it’s very popular in many countries still today. It seems like the public broadcasters in Europe just can’t get people to stop using it, no matter what new services they provide.

You most likely know teletext in the British version, with blocky text graphics in few colours, that came intertwined with the analogue TV-signal. This is called World System Teletext. But that was only the beginning. Teletext came in vector and pixel graphics, it was used for games and multimedia… there was even FM and PCM audio for teletext in Japan!

When you take a global perspective on teletext, it’s actually quite hard to say what teletext is. But let’s start in the UK in the 1970’s, when teletext was used for subtitles and text-based screens that you could flick through with your remote control.

Young teletext

In 1971, Philip’s engineer John Adams wrote a technical proposal to use the “invisible” part of the TV-signal (VBI) to transmit closed captions for the hearing impaired.* This was the starting point of three government bodies in the UK developing their own standards. BBC and IBA developed their own systems, agreed on a common standard (p.106), and launched Ceefax (1974) and ORACLE (1978) respectively. The third standard was the videotex-standard Prestel from the British Post Office.

Teletext Level 1 (1976) featured two character sets: a basic ASCII-like one, and a graphical one with so-called sixels. The screen was 40×24 characters and there was a palette of 7 predefined colours. Control codes, like switching between colours or character sets, required using an empty character on the screen. Level 1.5 (1981) added support for national character sets and it remains the most widely used teletext standard today. These British standards became known as World System Teletext (WST).

🡆 UK teletext posts

🡆 Galax Teletext lets you teletextify your website

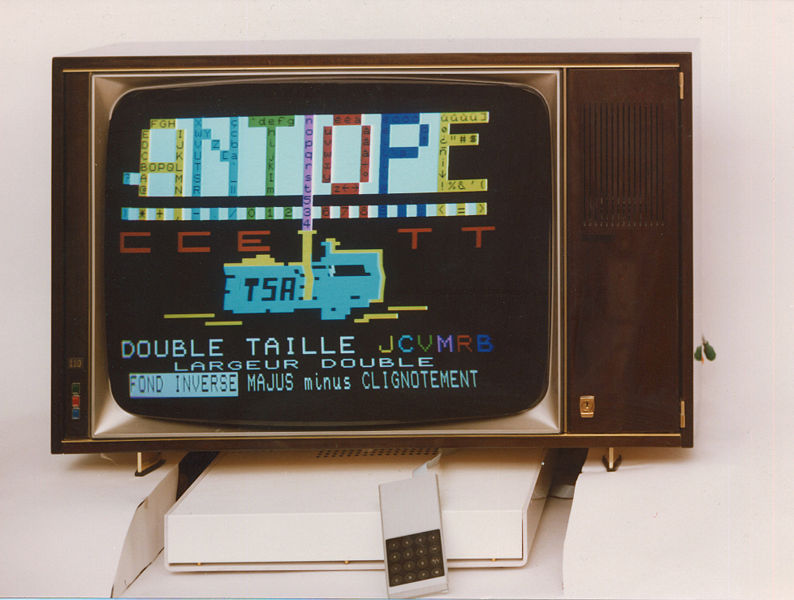

There was a teletext alternative that offered slightly more sophisticated graphics than WST did: the French Antiope standard, also developed in the 1970s. It was based on telecommunications (data packets) rather than a stream of TV-frames, which made it more flexible with control codes. It offered background colours and a variable font size already around 1977, as seen below and in a German news clip.

Antiope was a clever standard, and it had political and cultural signifance fo France. The American dominance in information technology, telecommunications and satellites after World War II was considered a threat to French national soveiregnity.* The Antiope technology formed a response to this perceived threat, but the real challenge was to establish it on the market. There was considerable rivalry with the UK, which apparently made the two countries “the laughing stock of the videotex world”. (p.133) Most TVs in Europe would eventually be equipped with British decoders, and very few countries used Antiope for teletext.* But guess what? One of those countries was France’s nemesis, the United States of America.

🡆 More Antiope graphics

Before we go there, let’s clarify something before we go deeper. There is a difference between the display level and the transmission level. Teletext graphics (display) can be used for videotex transmission, and videotex graphics can be used for teletext transmissions. France’s Antiope standard could be used for teletext as well as videotex. And teletext doesn’t have to use the blocky graphics that we know from the UK, as we’ll see soon.

| Display | Transmission | |

| Teletext | Usually basic textmode, but also vector graphics, etc | Normally one-way information using TV-broadcasting, but not always |

| Videotex | Enhanced textmode or vector graphics, but also pixel graphics | Usually two-way telecommunications, but also local terminals, etc |

Canada

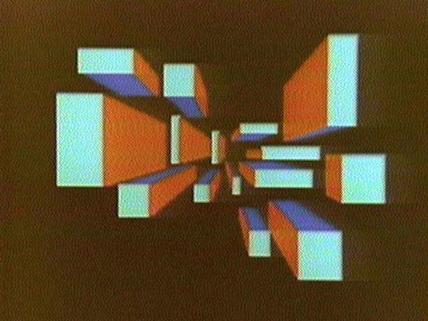

Canada’s government laboratory CRC developed Telidon in the 1970’s. It was designed both for teletext and videotex and used its own form of vector graphics called PDI. It was launched in 1978 and numerous trials were carried out in Canada for a few years. The complex graphics required a $2,000 decoder for the user, which was a bit hefty for a one-way teletext service, so we will return to Telidon later in the videotex section.*

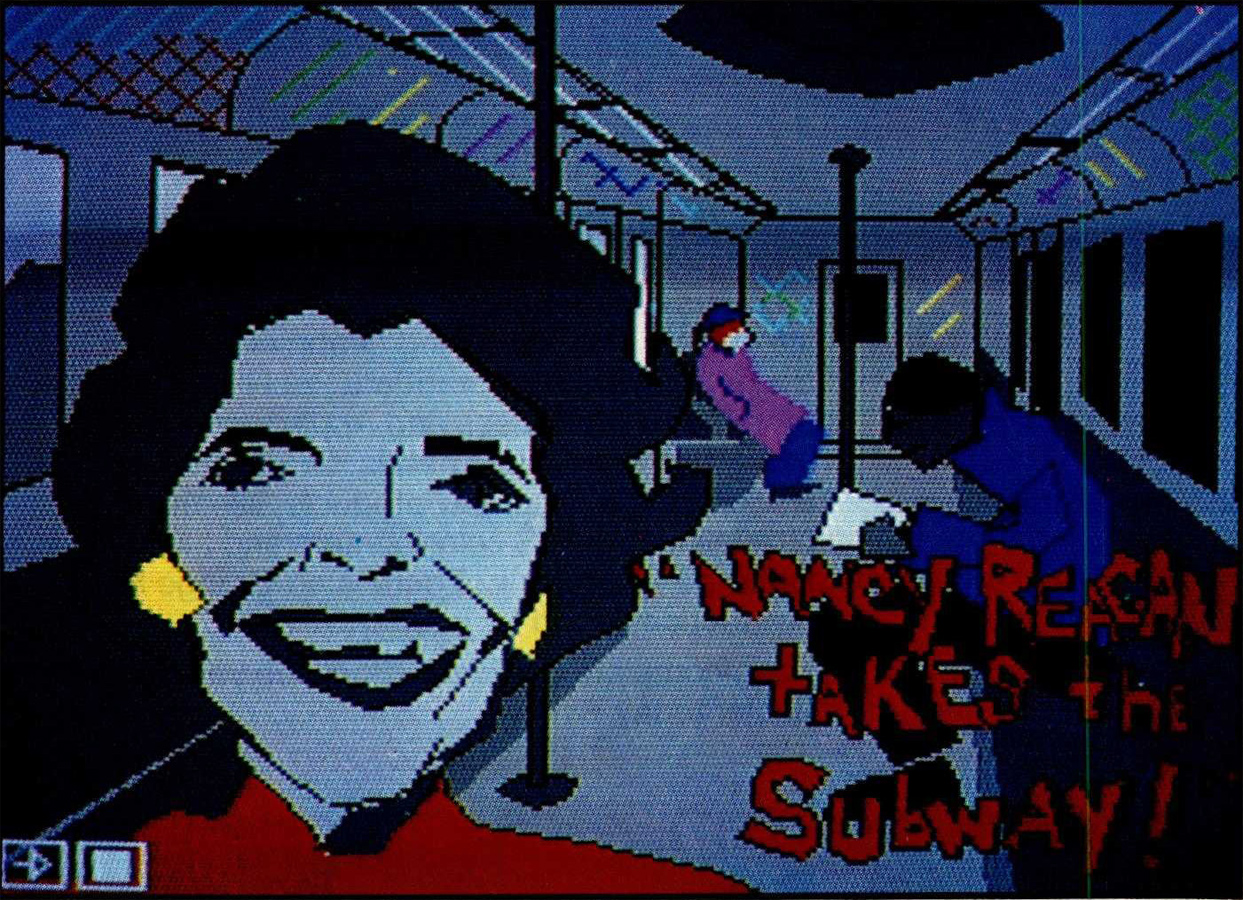

Teletext goes to Hollywood

While Europe managed to settle on one teletext standard rather quickly, aided by national public service monopolies (p.19), and Canada had gone all-in on Telidon, it was more complicated in USA. Reagan promoted de-regulation and the the national agency FCC, which normally regulates US tech-standards, were taking a step back when it came to teletext.**

Early American teletext entrepreneurs had three choices: Antiope, WST and Telidon. (Micro TV was a rarely mentioned predecessor*) The televisions sold in USA supported the British WST-standard, if they supported teletext at all. But the British system had not yet been adapted for the American TV-standard, so it was risky for teletext entrepreneurs to go for WST.* As I understand it, Zenith was the only TV-manufacturer in USA that supported WST, so it was a chaotic situation for both producers and consumers.* Which TV supports which standard now, and how about next year?

🡆 Good read on teletext in the USA

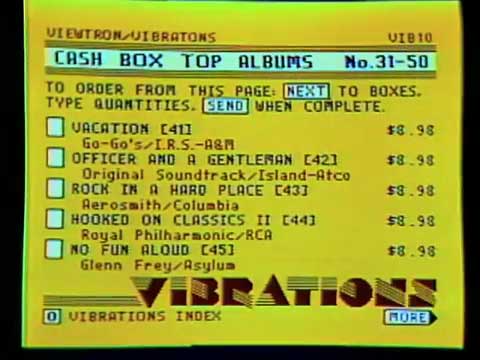

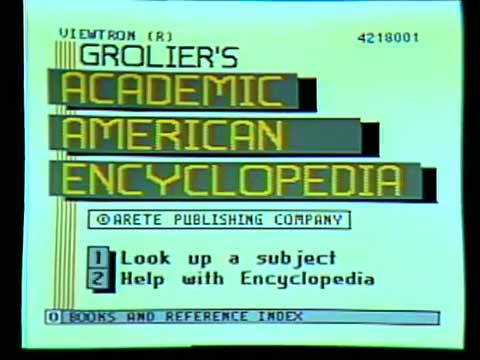

CBS ran tests in 1979 to compare Antiope and WST, and encountered several problems with WST. They decided on Antiope, and petitioned the FCC to adopt their modification of Antiope as a national standard.* Meanwhile AT&T, whose early experiments later led to the notorious Viewtron videotex, announced their own display standard in 1981-1982. (p.28) It was called PLP and it was based on the vector graphics of Telidon, while also supporting enhanced textmode graphics.** It added features for changing the font (DRCS, see below), spacing text proportionally and creating graphics macros (such as a logotype) and pasting them.* (details on p.82)

PLP was endorsed by major teletext/videotex companies in USA, who eventually got CBS on their side aswell. Canada came on board and US organizations such as ANSI, CSA, EIA and the Videotex Technical Experts Panel all worked towards a new standard based on PLP. The focus of the standard was primarily vector graphics (for videotex), but also included textmode graphics (for teletext). The purpose was to have one single standard for both teletext and videotex.* In 1983 it became the national standard NAPLPS (North American Presentation Layer Protocol Syntax)* which covered the display level. The transmission level standard (for teletext) was not formally standardized as NABTS until 1986.

A competition without winners

When you read about the history of NAPLPS, you will notice that there are two different ways to do it. One way is to frame it purely as a US invention. Telidon and Antiope are either completely omitted, or they are mentioned as something that was replaced.* But that seems unfair. Without the publicly funded research and development of France and Canada, NAPLPS would be something else, if it would exist at all. It has been claimed that NAPLPS was “heavily derived” from Antiope and Telidon.** Or even worse.

Telidon became the international standard that Canadian investors dreamed of. It was the foundation of the Canada/US North American Presentation Level Protocol Syntax (NAPLPS), which spread around the globe. Unfortunately, the code was changed deliberately so that all of the Canadian equipment and most of the content became useless, thus wiping out the competitive lead investors were counting on. Ironically, the winner, NAPLPS, rapidly became the loser when personal computers and the internet rolled over everything.

- Telidon Art Project website, 2024-02-26

The Canadian Telidon-artist Bill Perry describes Telidon as a $200 million boondoggle – a waste of money. Canadian public funding gave their companies an advantage over USA, something that the trade agreement NAFTA was designed to prevent, according to Perry, who concluded that “Telidon was the seed of NAPLPS and NAPLPS was the seed of NAFTA”* which seems like a beautiful exaggeration.

Public service Europe

Meanwhile in Europe, the French Antiope standard had already lost the battle against the British WST. Some countries tested Antiope, but only a few adopted it.* France did, of course, and they managed to keep it going until the early 1990’s when they finally switched to WST.* Their Antiope videotex, on the other hand, was a huge success, but more about that later.

The British WST-standard was used in 41 countries by some accounts (p.116), although I think the number is closer to 21.* It was relatively simple and cheap to implement, since the infrastructure was already there and most TV-manufacturers supported it. There were some regulatory issues, especially concerning ads and conflicts with the news media, but WST teletext was embraced politically by most countries in Europe. It became almost emblematic for European public service, and it is still around today, some 40 years later. At least 15 countries* broadcast teletext today (2024), with the same blocky graphics and a significant amount of daily users.

It is often assumed that teletext was mostly a thing in Western Europe, but that is not the case. Before we go East beyond the iron curtain, I’d like to mention Turkey. There are captures of very cool Turkish teletext graphics from the 1990’s.* Yugoslavia is even more interesting example, as a communist country that was not aligned with the Soviet Union. Yugoslavia launched a national teletext in 1984 and Croatia started their own teletext service just before declaring independence in 1991. It became an important source of information during the war.**

Back in the USSR

The Eastern Bloc was generelly late to adopt teletext, except for Hungary (1982). Germany is an interesting case, since the iron curtain went right through it in the 1980s. The TV broadcasts from West Germany’s reached East Germany (GDR) and therefore the Eastern Bloc. So GDR developed their own TV-stations and aired programs like Der schwarze Kanal that re-edited news from the West and added a communist commentary. But they did not broadcast teletext, because there were very few TVs in the country that supported it. However, there were test broadcasts as late as 1989, preserved by the Videotext museum.* (the old German term for teletext is videotext, confusingly)

Poland started with teletext broadcasts in 1988, the year before they exited the USSR. I have not been digging into it much, but I did find an odd commercial for the Polish Mediatext teletext and its erotic teletext services, supposedly from ca 2010 (if it’s not fake?).

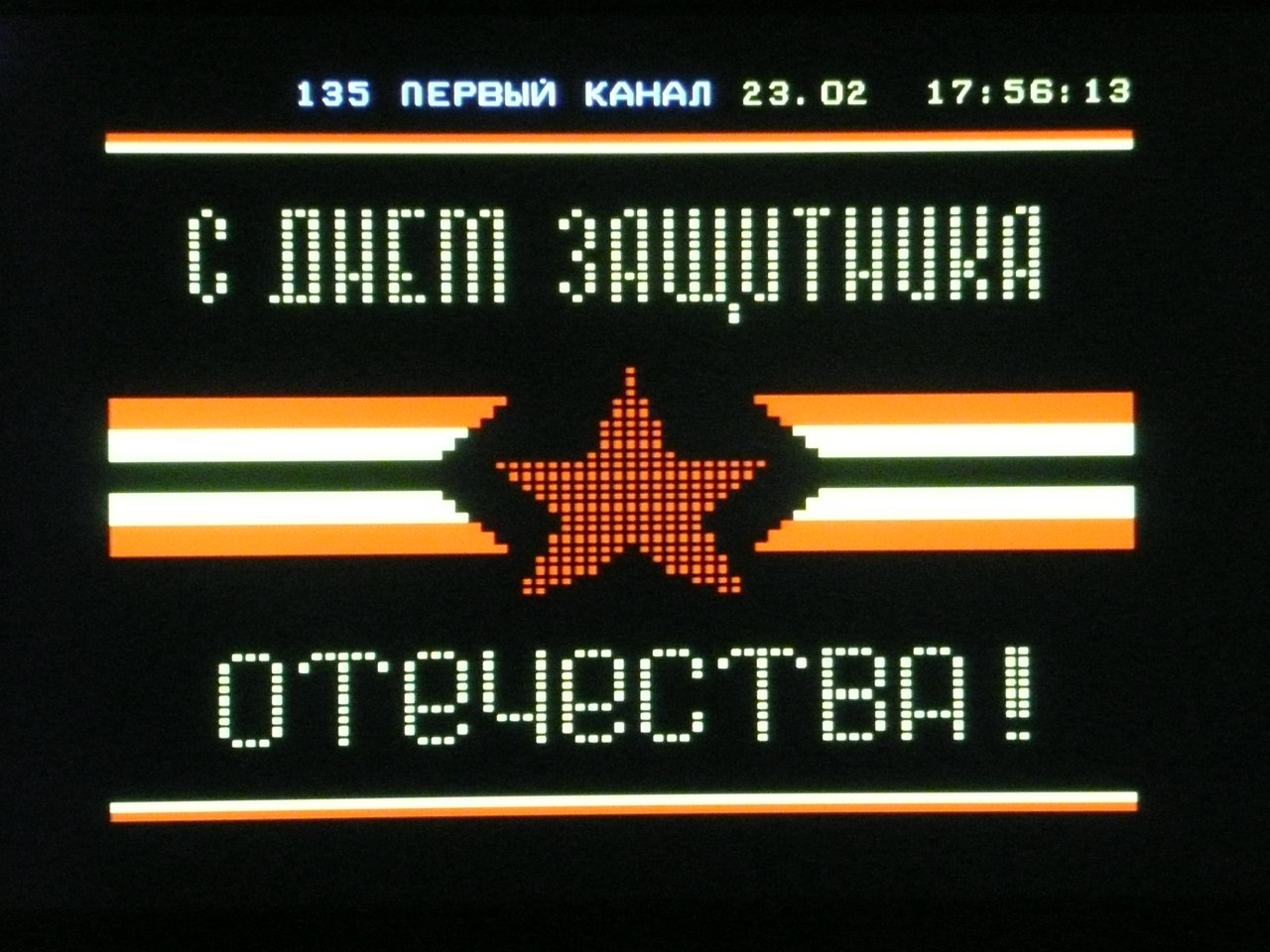

While browsing the internets for teletext in various countries, I didn’t come across much information about broadcasting your own teletext. I wasn’t expecting to. But it seems to have been different in Russia. This hobbyist site explains how to use a teletext generator and how to apply for the right permissions to broadcast it. One of the suppliers of the teletext generators, Wladimir Solovjev, started to broadcast his own teletext service in 1991 or 1992. It was called Peterburgksiy Teletext and it was active for 15 years. It seems to have been a small teletext-only media company, broadcasted by three different local channels.*

We started broadcasting in this format on television channels back in 1991. I was the first to do this on a significant territory of Russia. Later, teletext appeared on the First Television Channel, with our help.

- Wladimir Solovjev, e-mail correspondence 2024-02-26

The British journalist Steve Rosenberg was involved in the official national teletext in Russia, which he talks about in this podcast.

Two more unusual things about Russian teletext is worth mentioning before moving on. 1) Someone hacked a Russian teletext service to add anti-war messages on Victory Day 2022, according to this. 2) New teletext services continued to appear well into the 2000’s, such as MTV Russia in 2006-2007.**

English is not enough

A fundamental issue with WST was that the character set was initially only basic Latin, which is not good for much else than English. WST had to be adapted for other languages, which was not difficult in countries like Sweden, Hungary (although, there are Swedish characters in this video?), Netherlands and West Germany. It was “just” a matter of adding a few characters.** Some countries settled for not having a full character set, like Yugoslavia who in 1984 didn’t have any diacritics.*

It was more work to adapt WST for Arabic, Cyrillic, Farsi and Vietnamese. It required custom hard- and software for WST to support these character sets, which is explained here by Colin Hinson who was part of creating systems for Vietnam, Russia and Ukraine. Vietnamese was particularly tricky, because it uses 134 Vietnamese characters in addition to basic Latin. That is too much for WST to deal with, but apparently they were able to fix it by simply removing 6 characters. :-)

But what about scripts with thousands of characters, which is common in Asia?

Meanwhile in Asia

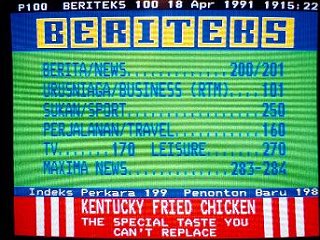

Singapore and Malaysia* were the first countries in Asia to broadcast teletext nationally in 1983 and 1985 respectively. Singapore published teletext in English and Malaysia in Malay, but they both used WST and the Latin script. Examples are available at the Teletext Museum.**

Meanwhile, Japan was one of the leading tech countries in the world, and had no reason to limit themselves to 128 characters. They had established their ASCII-compatible JIS-standard already in 1969 and since then worked on a combined hardware for (what the West would call) teletext and videotex (p.20). The Japanese engineers needed to create a system that would cater for thousands of characters, but also a font that was big enough to represent the intricacies of the characters. The 128 characters and 6×10 pixel font of WST was not nearly enough.

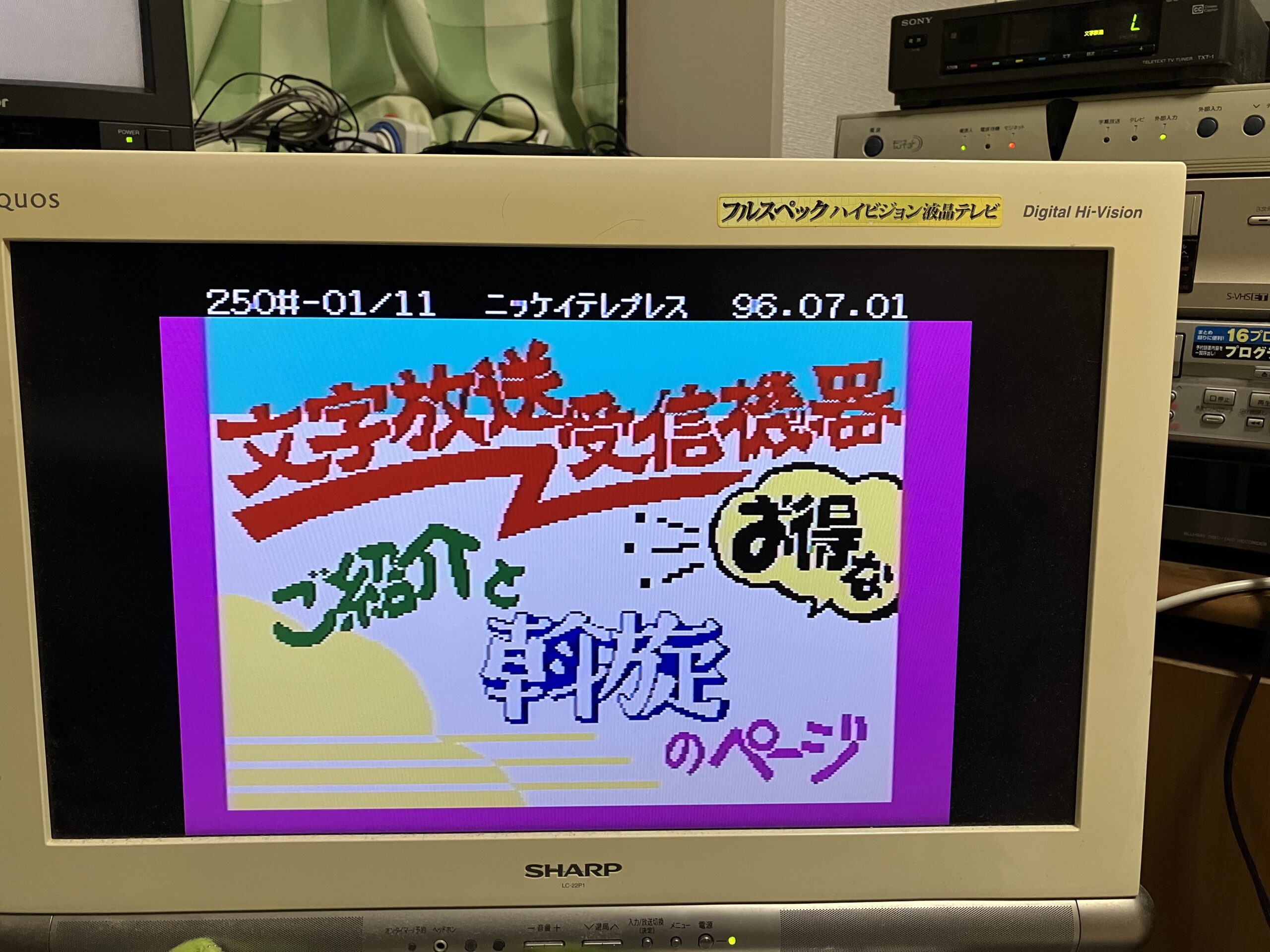

In 1978 NHK began experiments with a so-called pattern method called CIBS: full screen pixel images in about 350×200. [1] Trials started in 1983, but in 1985 a decision was made to use a hybrid method instead which combined pixel images with text. This became JTES, one of four global teletext standards in 1986.* It supported kanji, katakana and hiragana characters using an 8×12 font, with a screen resolution of 8×15 characters.* Any missing characters missing in the font could be added with customizable characters (a technique called DRCS). Vector graphics similar to NAPLPS was supported, and JTES also offered pixel graphics in a resolution of 248×200, although it was slow to load, especially with many colours (p.21). Finally, JTES supported sound. It could use an FM-soundchip or PCM-samples using the so-called BEST system.*

All in all – JTES seems to have been on a different level than Europe and USA, although I don’t know if all these features were available from the beginning. Perhaps the answer is to be found in the incredibly dense Japanese Wikipedia page on teletext. Let me know if you manage to get through it…

In South Korea, Munhwa Broadcasting (MBC) launched teletext in 1988 and used the Japanese JTES standard.*

🡆 More Korean teletext posts

China never really used teletext, although they did develop their own technologies and tested them on several channels.* They made a new standard based on WST, called CCST. It supported 3000 characters and drew the rest as pixel graphics. CPLPS was based on NAPLPS and featured Chinese characters and vector graphics. Learn more

Hong Kong was early to adopt videotex, and it was heavily used in the financial industry. Financial data was produced, distributed and refined in a complex ecosystem of networks, protocols, providers and services.* One service could be available as (interactive) videotex for TVs or computers, and as (non-interactive) teletext broadcasted as real teletext or as video (so called in-vision). The boundaries between videotex, teletext and ASCII-based services, seems to have been so blurry in Hong Kong that it didn’t even make sense to use this terminology. Networks, providers, services, videotex, teletext, telex, pagers, TV-broadcasts, datastreams… Who is doing what where? Read this to join the confusion.

🡆 More examples of Asian teletext services

Teletext in the Middle East

I haven’t researched this area very well. But Israel launched a teletext service in 1986. Gulfax in the United Arab Emirates offered teletext in Arabic in the 1980s* and in English possibly in the 1990s.* Egypt and Iran had teletext for sure, and the pan-Arabic tv-channel MBC was broadcasting teletext in Arabic.* Jordan had something, possibly only in-vision. Kuwait, Oman and Syria possibly offered teletext as well. If you know anything more about Middle Eastern and/or Arabic teletext, please get in touch. Also see this.

Elsewhere

Oceania had teletext in Australia and New Zeeland. Africa had teletext in South Africa and possibly in Burkina Faso, Malawi and Morocco. In South America I’ve only managed to confirmed teletext in Brazil, but it was possibly available in other countries too.

More information is available in my list of teletext/videotex services.

Teletext standards and names

The CCIR defined the following standards in 1986. The countries listed below have adopted the standards according to ITU* (1998) and Video Demystified* (2005, page 178) , but it is unclear to what extent it was used. As far as I can understand, these standards include both the display and the transmission.

- A – Antiope (France, Colombia, India), transmitted with Didon (p.4)

- B – World System Teletext (Australia, Belgium, China, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, (West) Germany, Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, Malaysia, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Yugoslavia)

- C – NABTS (USA, Canada, Brazil) typically displayed with NAPLPS

- D – JTES (Japan)*

World System Teletext Level 1.5 from 1981 is still the most widely used standard for teletext, despite numerous new enhanced teletext standards over the years, sometimes called HiText.*** The most recent one in Europe is Level 3.5 from 1997. So-called digital teletext such as NTL’s Digital Plus (UK, 2000) and more recent incarnations for the HbbTV, are perhaps the pinnacle of the “attractive” teletext that ETR outlined with HiText – and they do indeed offer some very cool potentials for text graphics. However, classic teletext is apparently hard to top, and even in the 2020’s it is used daily by 10-15% in several countries in Western Europe. (see below)

Most countries call it teletext, but there are exceptions. In Scandinavia they often go by Text-TV, in Germany and Switzerland it is sometimes called videotext, Italy calls it televideo, and in Iceland it’s called textavarp (text broadcast).

What about all the smut?

There is no lack of x-rated material on teletext, which might come as a surprise to some, given the rudimentary graphics. I’m not sure if it’s mainly a European thing, but over here commercial teletext channels have loads of explicit ads for dating, sexy chat and phone services, etc. A Polish ad from circa 2010 even seems to push this as a key selling point.

🡆 All x-rated teletext posts in this blog

🡆 Teletext Babez by drx

🡆 Polish ad for teletext (if not fake?)